Special Feature

A Sacred Journey of Rebirth: Historic Hike in the Dewa Sanzan Holy Mountains

The Dewa Sanzan holy mountains, designated as a Japan Heritage site in 2016, are the training grounds and center of Haguro Shugendo, a form of Japanese mountain asceticism practiced here. Visiting the three mountains of Mt. Haguro, Mt. Gassan and Mt. Yudono is called a journey of rebirth following a cycle of death and being reborn. A uniquely Japanese form of worship is found here at the Dewa Sanzan holy mountains, where people have been coming to worship the nature that they both fear and revere for some 1,400 years.

We’re going to follow Rena Otsuki and Everett Brown, who experienced yamabushi mountain monk training, and Fumihiro Hoshino, a master of Haguro Shugen mountain asceticism, as they climb Mt. Haguro. The trio will embark upon a sacred journey of rebirth using a historic path that was opened in the Edo Period (1603–1867).

On a morning with rain dripping from green leaves, the three set off from Daishobo, one of several lodgings in the town of Toge for pilgrims heading to Mt. Haguro, to leave the secular world behind and step into the sacred realm. Yamabushi mountain monks train by trekking in silence, but today the group will climb the mountain while learning about its nature and history.

Zuishinmon Gate

The Zuishinmon Gate marks the entrance to the pilgrimage route and the sacred area that lies beyond. According to Hoshino, “The atmosphere feels different on the other side of the gate. That’s because the space has received the prayers of so many people.” Shugendo is a form of mountain worship, one type of nature worship practiced in ancient Japan, that combines elements of Buddhism, Taoism, Shintoism, Confucianism and other faiths. Its practitioners undergo grueling ascetic training in the mountains with the goal of obtaining enlightenment.

The Dewa Sanzan holy mountains are considered sacred and have been objects of worship by people since ancient times as manifestations of Buddha in the form of Shinto kami, or gods. The Shinto and Buddhist religions were long intertwined in Japan, but in 1868 the Meiji government enacted laws to separate them and thereafter the Dewa Sanzan holy mountains were designated as Shinto kami. Up to then, the kami here were considered manifestations of Buddhist gods, with Mt. Haguro representing the Shokanseon-bosatsu (The Buddha of Worldly Benefits), Mt. Gassan representing Amitabha (Buddha of the Salvation in the Afterlife), and Mt. Yudono representing Dainichi Nyorai (Symbol of Eternal Life). Worshippers pray for favor in this life at Mt. Haguro, pray for peace in the afterlife on Mount Gassan and pray for their reincarnation at Mt. Yudono. This journey of rebirth gained popularity among the common folk during the Edo Period and is still undertaken by people today.

Otsuki describes her first experience of yamabushi mountain monk training like this. “Feeling the depth and fearsome power of the natural world and being reminded that I am a part of it brought back the pure physical sensations that I had as a young child.” She says these sensations helped recenter and prepare her for this journey of rebirth.

Passing through the gate, the three enter Mt. Haguro, the sacred mountain of the present world among the three mountains of the Dewa Sanzan.

Harai River

The cedar-lined path to the top of the mountain consists of a 1.7-kilometer stone staircase with some 2,446 steps. Under Tenyu (1595–1675), the 50th chief priest of the Dewa Sanzan holy mountains, the stone steps were laid on Mt. Haguro starting in 1648, a massive undertaking that lasted 13 years. After passing through the Zuishinmon Gate, visitors encounter a steep downward descent called Mamakozaka. This symbolizes the path to the abyss that goes down to the depths of hell. In Buddhism, this metaphor expresses that only those who have performed ritual purification called “misogi” can reach the top of the mountain symbolizing the Pure Land. The Harai River is said to be the Sanzu River in Japanese Buddhism, akin to the River Styx separating the worlds of the living and the dead, and is where Shugen practitioners purify their bodies before entering the mountain. This was Everett’s favorite place on the mountain, where he “could feel the energy brought down from the mountain by the water.” “Water and vegetation are the wonders of Japan. You can feel the seasons changing every five days or so. When we arrived at Haguro yesterday, the air smelled of a green that defies categorization as spring or summer,” reflects Everett.

After crossing the Shinkyo Bridge over the Harai River, they start their ascent up the mountain. Among the grove of cedars which date back over 300 years, stands Jiji-sugi (“Grandpa Cedar”), said to be the oldest cedar of them all at more than 1,000 years old. Hoshino says that “Trees are the gods that connect the heavens to the earth.” Lined up seemingly in symmetry with Jiji-sugi, a symbol of a nature kami, is the Five-Storied Pagoda, a National Treasure built by the skilled hands of men.

Five-Storied Pagoda and the Southern Valley

Made of unvarnished wood, this five-storied pagoda with a wood-shingled roof, measures in at just over five meters per section for a total height of 29 meters and is the only five-storied pagoda designated as a National Treasure in the Tohoku region. Hoshino comments, “When people long ago sensed the presence of the gods, they devoted themselves to building paths and pagodas. Foreign visitors to the Dewa Sanzan holy mountains say they feel inspired when they come here, and it is the prayers of people that form the basis for this. Sensing the spiritual energy of this sacred place takes on special importance in our modern world.” “Even if you don’t have worldly possessions, being able to sense the beauty in the everyday and changes in the natural world lend a richness to life. Shugendo training opens people to these perceptions,” muses Everett. Leaving the Five-Storied Pagoda, they embark up a long ascent called Ichinosaka slope. This path is also the path of birth, where you experience the pain of being born with your body. The sky seemed to open up and welcome them with rays of sunshine as they approached the steep Ninosaka slope.

Just before the Sannosaka slope, they turn right and take a detour. After walking for about 10 minutes, the shadowy cedar forest suddenly gives way to a lush green vista that unfolds before them. This is the Southern Valley, where the remains of Betsuin Shion-ji Temple, the former residence of the chief priest, are located. “On Mt. Haguro, the forest canopy only opens up here and at the summit,” notes Hoshino.

Now it is finally time for the highest point of Dewa Sanzan worship. For Shugendo practitioners, the Sannosaka slope is the last challenging leg before going under the torii gate at the top of the mountain.

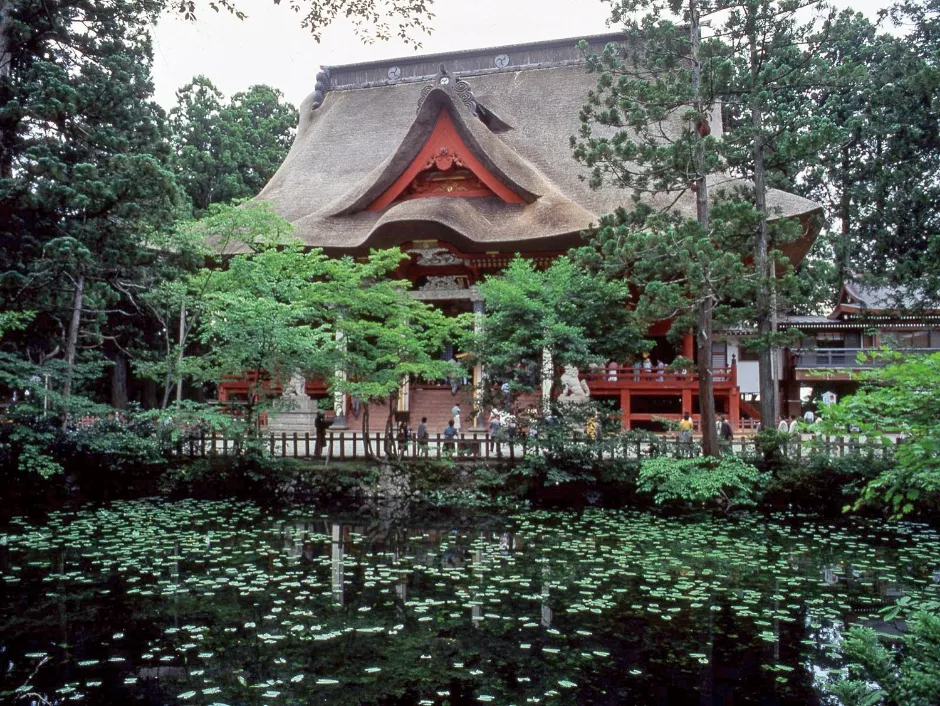

Top of Mt. Haguro

At the top of the mountain, which symbolizes the Shokanseon-bosatsu (Buddha of Worldly Benefits) and the Pure Land, sits the Sanjin-Gousaiden Shrine, where the three deities of the Dewa Sanzan holy mountains are enshrined: Tsukuyomi-no-Mikoto, Ukanomitama-no-Mikoto and Oyamatsumi-no-Mikoto. The magnificent main building features a thatched roof that was rebuilt in 1818, and paying your respects here serves to also pay your respects to all three mountains. “Gousaiden was built in the time when Shinto and Buddhism were fused together, and the building is both a Shinto shrine and a Buddhist temple. Our predecessors protected the ancient Shugendo practices even after Shinto and Buddhism were ordered to separate. This epitomizes the beliefs of the Dewa Sanzan. Our predecessors offered prayers to this mountain as living beings, as their souls dictated,” explains Hoshino. “Japan has many ‘-do,’ or ‘ways,’ such as sado (the way of tea) and bushido (the way of the warrior). They are not only about refining one’s skills, but also call to the practitioner to question their fundamental state of mind. Shugendo is also certainly one of these ‘ways.’ Even overseas visitors can understand the essence of the Japanese traditions and spirit expressed through Shugendo. I feel how it quietly yet powerfully teaches us that we are all alive on this planet together,” remarks Otsuki. “For me, the Dewa Sanzan are an experience that transcends time. Your ego melts away amid the untamed forces of nature and becomes part of it, becoming just a life form. This sense of unbridled freedom is what I love about Japan,” comments Everett.

This journey of rebirth, trekking among cultural properties while enveloped in the spiritual energy of sacred mountains, is a rewarding way to refresh both your body and your soul.

-

-

-

-

Japanese people have long believed that kami live among us and in nature and have prayed to them. The yamabushi mountain monks have the word “uketamo,” which symbolizes the Dewa Sanzan holy mountains. It has the meaning of accepting everything—Shinto and Buddhism and all living things. (Hoshino) -

Street with pilgrim lodgings in Toge -

Zuishinmon Gate at Mt. Haguro -

Stone staircase on Mt. Haguro -

Cedar trees on Mt. Haguro -

Jiji-sugi (“Grandpa Cedar”) on Mt. Haguro -

Five-storied Pagoda on Mt. Haguro -

Mt. Haguro’s Southern Valley -

Sanjin-Gousaiden Shrine on Mt. Haguro