Special Feature

Zenpo-ji Temple, 365 Days of Prayers

Dedicated to Ryujin (naga gods), the protectors of the sea, Ryutaku-san Zenpo-ji Temple has been revered as a place of worship for all kinds of people, especially those connected to the fishing and maritime shipping industries. Zenpo-ji Temple is one of the three most famous Soto Zen Buddhist prayer temples in Japan. The Soto school of Zen Buddhism was brought from China and founded in Japan by the Zen master Dogen some 800 years ago. Prayers are offered 365 days a year at Zenpo-ji Temple, with the morning of New Year’s Day and the beating of the prayer drums heralding the first of the year’s ceremonies.

Let’s dive in to the history of Zenpo-ji Temple to get a clearer picture of the legend of the Ryujin (naga gods), and the religious faith that dwells in the hearts and minds of the people who come here to pray.

Zenpo-ji Temple and Its Faith

Zenpo-ji Temple’s history dates back to 951, when the Buddhist monk Myotatsu Shonin initially built a simple hermitage here. The temple got the name Zenpo-ji Temple in 1447, around 500 years after this retreat was founded. We asked Takuzo Igarashi, formerly the 42nd abbot of Zenpo-ji Temple, to explain more about this fascinating location, and how it functions as both a Soto Zen Buddhist temple and also a place where Ryujin are worshiped and enshrined.

“In ancient China, Ryujin was believed to be the guardian god of production who controlled water sources and was therefore worshipped mainly by people who worked in the marine products and fishing industries. How this belief spread is unclear, but worshipping at Zenpo-ji Temple became a widespread practice during the Edo Period (1603–1868). The faith was particularly prevalent among people working on Kitamae-bune merchant ships sailing around the Sea of Japan and net fishermen originally from the Shonai region who expanded into herring fishing in Hokkaido.”

People were seeking out something awe-inspiring, and Zenpo-ji Temple was a place of worship that gave them this. “Sutras were born from the land. The creation myth dominant in the West says God created everything from nothing. Meanwhile in the East, forests of trees thick with leaves that would fall to the ground gave rise to the idea of impermanence and generation myths founded in nature. Western religions are monotheistic, while Japan has a countless number of gods and goddesses. Among them Ryujin was believed to be the protectors of the sea. The worship of these sea deities has permeated throughout the entirety of Japan.”

A symbol of this nature worship is the Naga Sutra that is unique to Zenpo-ji Temple. The serpent deity Naga from India and Dragon King worship from China fused together to become Ryujin (naga gods) in Japan. “The skies would darken and the clouds would bestow the gift of rain. Sometimes it would fall gently, other times heavily, and so people in ancient Japan must have believed this was the work of giant Ryujin in the clouds. In this way Japanese people have learned from nature. It is the very spirit of the Japanese people and a part of our culture that we should take pride in.”

Japanese people’s take on nature and religion is that gods reside in nature. People project living forms onto the changing quality of the natural world. “Just like the flowing of a river, we also transition from one thing to the next. What we can get within this movement is enlightenment.” Igarashi says that to achieve enlightenment, “Always moving forward with a state of mindfulness is important.” Having clear awareness in everything you do will lead to self-enlightenment and, by extension, a clear understanding of your own path in life.

Temple of Daily Prayers

Zen teachings tell us that our daily mindset and behavior is our training. Zenpo-ji Temple is one of the three main Zen prayer temples and where Soto Zen monks undergo training. We asked Eiji Shinozaki, the head of public relations for the temple, what their daily training is like. “Prayer ceremonies are conducted every two hours at Zenpo-ji Temple, so monks in training have a daily routine filled with Zazen (shikan taza) meditation, tasks, lectures, and such in between the ceremonies. There are only a small number of monks in training at our temple, so they are able to experience various kinds of work while here. Being able to immediately handle things like memorial services after leaving the temple may be a special feature of Zenpo-ji.”

When trainees enter the temple, they first practice Zazen meditation for a period of five days. Only after that are they welcomed as a member of the temple and allowed to enter the meditation hall. They receive one tatami mat per person as their living space here. At this point, they are not allowed outside or to have any contact with the outside world for a period of 100 days. During this time, they learn a considerable amount about proper manner and work-related tasks. After the 100 days have passed, they are taught how to conduct memorial services and other rituals.

Kohei Yamamoto came to the temple in the spring of 2018 and is currently in training in order to inherit the temple his family runs in the future. “Soon after I began my training, I learned from my assigned teacher that within the very essence of our daily behavior, resides the teachings of Buddha. ‘Living itself is training,’ meaning that meals, cleaning, and Zazen meditation are all part of it and are connected to Buddha’s heart. I understand that this is something that lasts as long as I am alive, not just during training.” The kanji characters that make up the word for training have the meaning “to improve one’s actions,” and Shinozaki describes the meaning of his training like this. “I train to be like Buddha not only during Zazen meditation but each time I put my hands together in prayer, each time I raise and lower my chopsticks. This is the concept of ‘giving yourself over to the form.’ Trainees let go of all types of desire and surrender their body to the form. People let go of attachments, meaning the things they wish for, and leave these up to the gods and buddhas—this is prayer. The form of monks in prayer is the form of surrendering oneself to the gods and buddhas. So through monks, people surrender themselves to the gods and buddhas. This action is the prayer ceremony.” Training that begins and ends with Zazen meditation shows a way of approaching life where the mentality of always questioning your mind and taking action accordingly represents in itself, the Buddha.

Exploring the Art of Zenpo-ji Temple

You first step into the temple grounds by passing through the Somon Temple Gate, which was rebuilt in 1856. Serving as the master carpenter on this magnificent structure, Kaemon Kenmochi (floruit circa 1800) born in Tsuruoka City, was invited to come work at Zenpo-ji Temple while still in his 30s, after honing his skills as a carpenter, Buddhist sculptor, and painter in Edo (Tokyo) and Kyoto. He spent the next 48 years working on numerous buildings and sculptures. At the Sanmon Outer Gate, for which he also served as the master carpenter, you can still see the beautiful shishi guardian lion sculptures created in a competition between him and his younger brother Tomigoro Okuyama (1832–1890).

The Five-storied Stūpa to the right of the Sanmon Outer Gate was erected in 1893 by a team led by master carpenter Kanekichi Takahashi (1845–1894) to commemorate sea creatures. The central pillar inside the stūpa, which represents Dainichi Nyorai, a Buddha worshiped in Esoteric Buddhism, hangs down from the middle of the stūpa like a weight. It serves as a seismic isolation structure and is said to have protected the stūpa from many major earthquakes that have struck the region to date.

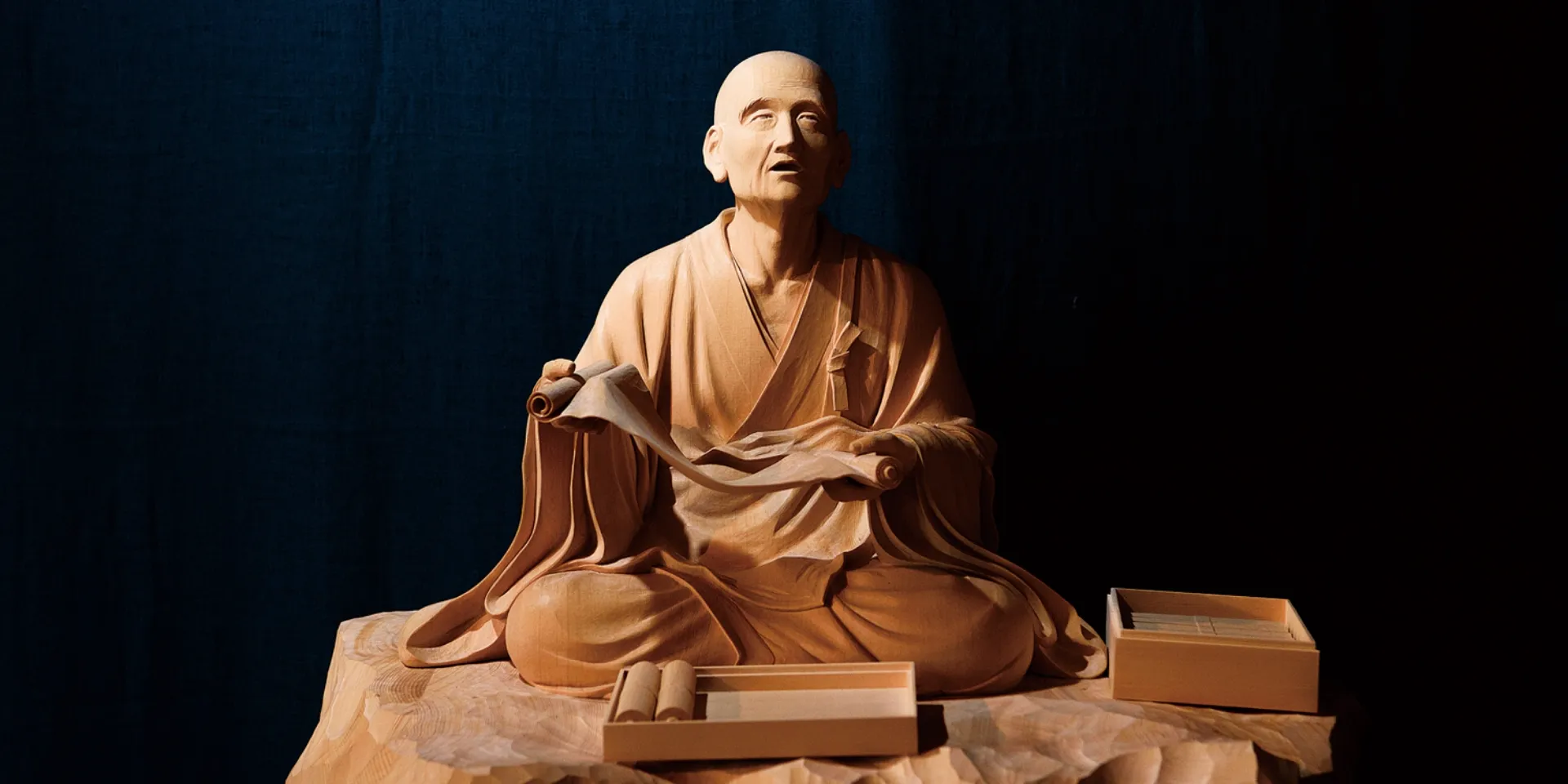

The Hall of the Five Hundred Arhats, which holds 531 Buddhist statues known as Arhats, stands to the right of the Sanmon Outer Gate. No two statues are alike, and back in the time before photography, people would find a statue whose face resembled a departed loved one and put their hands together to pray to it.

After climbing the stone stairs behind the Main Hall, you will see Ryuo Hall (Naga Shrine). This building is modeled after Ryugu-jo, the undersea castle of Japanese myth. Featuring ornate embellishments inside and out, Ryuo Hall has an unmistakably majestic stature.

Many other exquisite artworks can be found around the temple grounds, offering the opportunity to experience aspects of both Japanese faith and artistic sensibility. Some of them are also designated as Important Cultural Properties. This is a perfect place to take a stroll and refresh your spirit.