Special Feature

The Man Who Captured the Spirit of Japan in Photos—Ken Domon

Located in the northern reaches of the country on the Sea of Japan side, the city of Sakata is the birthplace of the renowned World War II and postwar-era photographer Ken Domon (1909–1990), who once wrote: “As a Japanese citizen, my own country fascinates me more than any other. My goal has always been to photograph the realities of life in Japan in a quintessentially Japanese way.”

True to his vision, Domon dedicated his life to portraying Japan and its people with a loving but unwavering gaze that spanned decades. More clearly than a thousand words, his photos reveal the essence of the Japanese spirit.

The Turbulent Times of Ken Domon, Photographer, and the Japan He Sought to Portray

Ken Domon encountered photography at the age of 24. The year was 1933, and Domon was feeling no hope for the future until his mother suggested as “a measure of last resort” that he try getting a job as a photographer. That turned out to be the push he needed, and the rest (becoming the preeminent Japanese photographer of his era) is history.

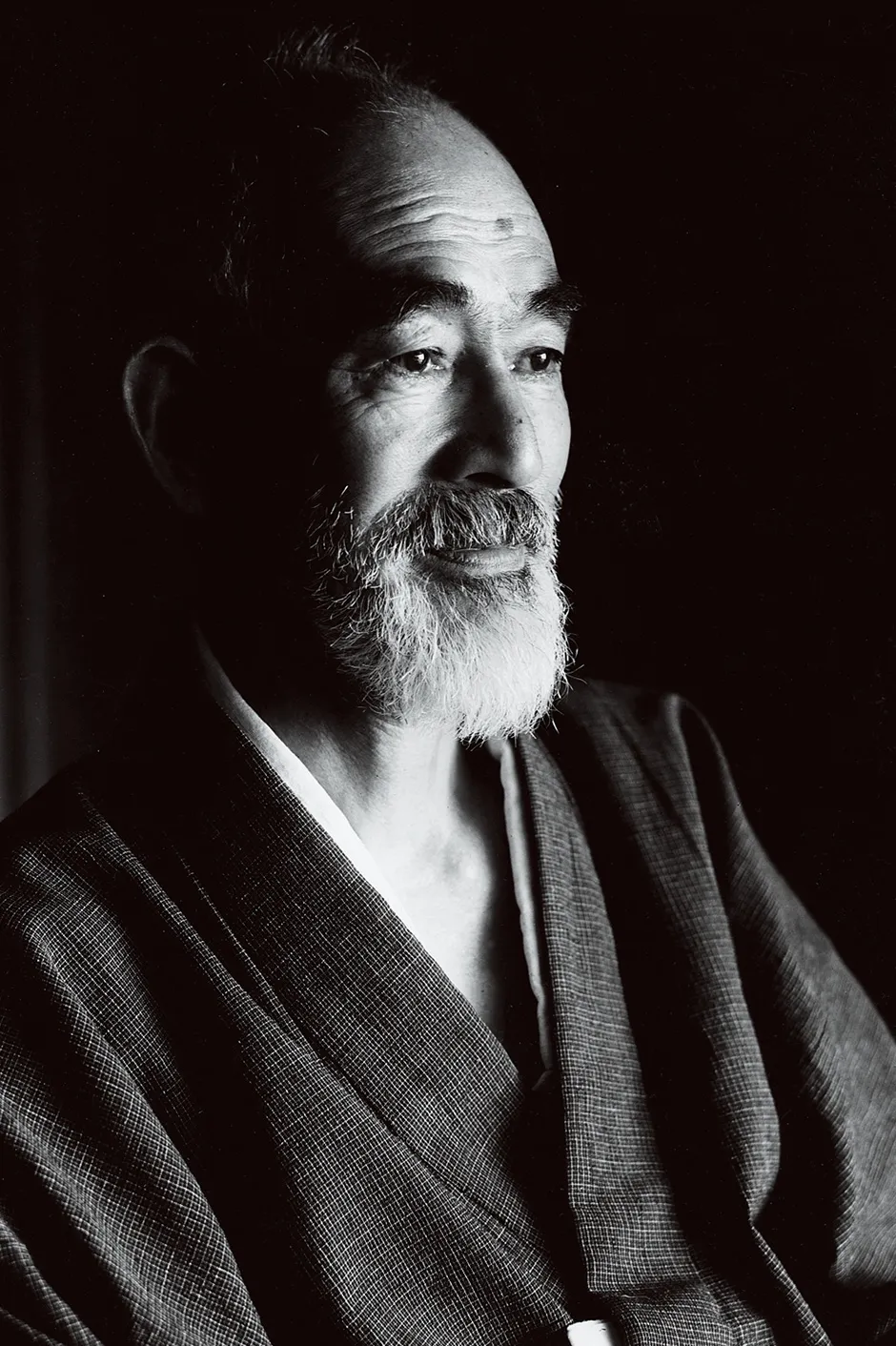

His most notable works include a series of portraits of Japan’s leading cultural figures. Known for his penetrating gaze, Domon would often fix his eyes on his subject, engaging in a long, silent dialogue, punctuated in the end by the click of the shutter, a decisive moment Domon acknowledged as a deliberate technique.

Domon’s career evolved as Japan entered another tumultuous period of great change, war, and modernization. Author Hiroyuki Abe, also a native of Yamagata Prefecture, who documented Domon’s life in a 1997 biography written in Japanese, explained, “When Domon became a photographer, Japan was on the brink of war, and photography was an important medium, so it was used for propaganda.”

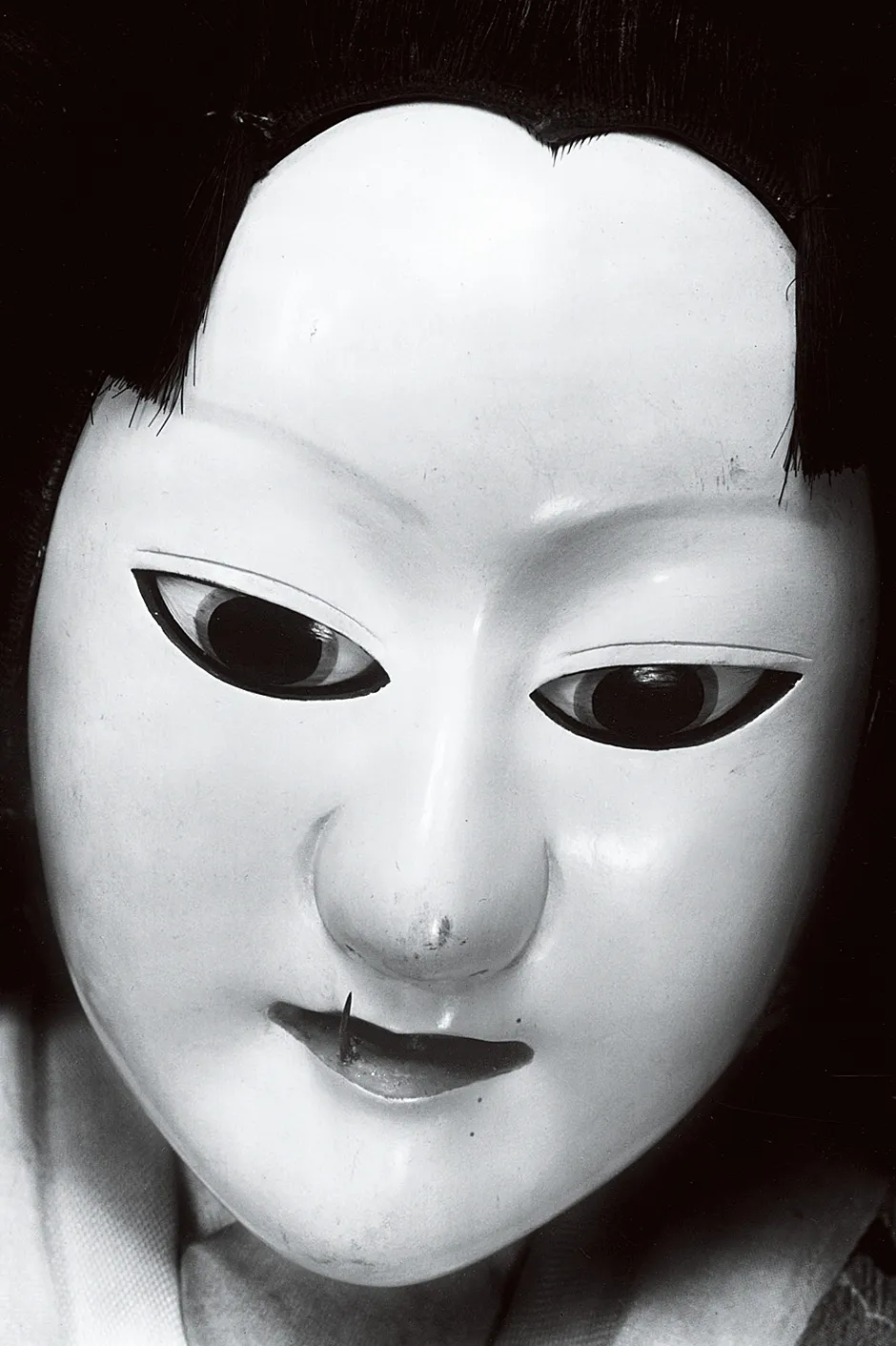

In defiance of the times, Domon immersed himself in photographing Buddhist statues and Bunraku puppetry. Recalling a visit for the first time in many years to Nara’s Muro-ji Temple after the war, Domon wrote, “The Japan I had lost sight of during the war reappeared before my eyes, vibrant and alive.”

Thereafter, he devoted himself to capturing the timeless beauty of Japan’s temples and statues.

In his book of photos focusing on the Buddhist statues of Japan, Domon expressed his belief in the intrinsic link between Buddhist statues and Japan itself, writing, “That single trip to Muro-ji Temple triggered a big decision. I felt that if I could photograph Buddhist states all over Japan, I could come to understand Japan’s history, culture, and people.”

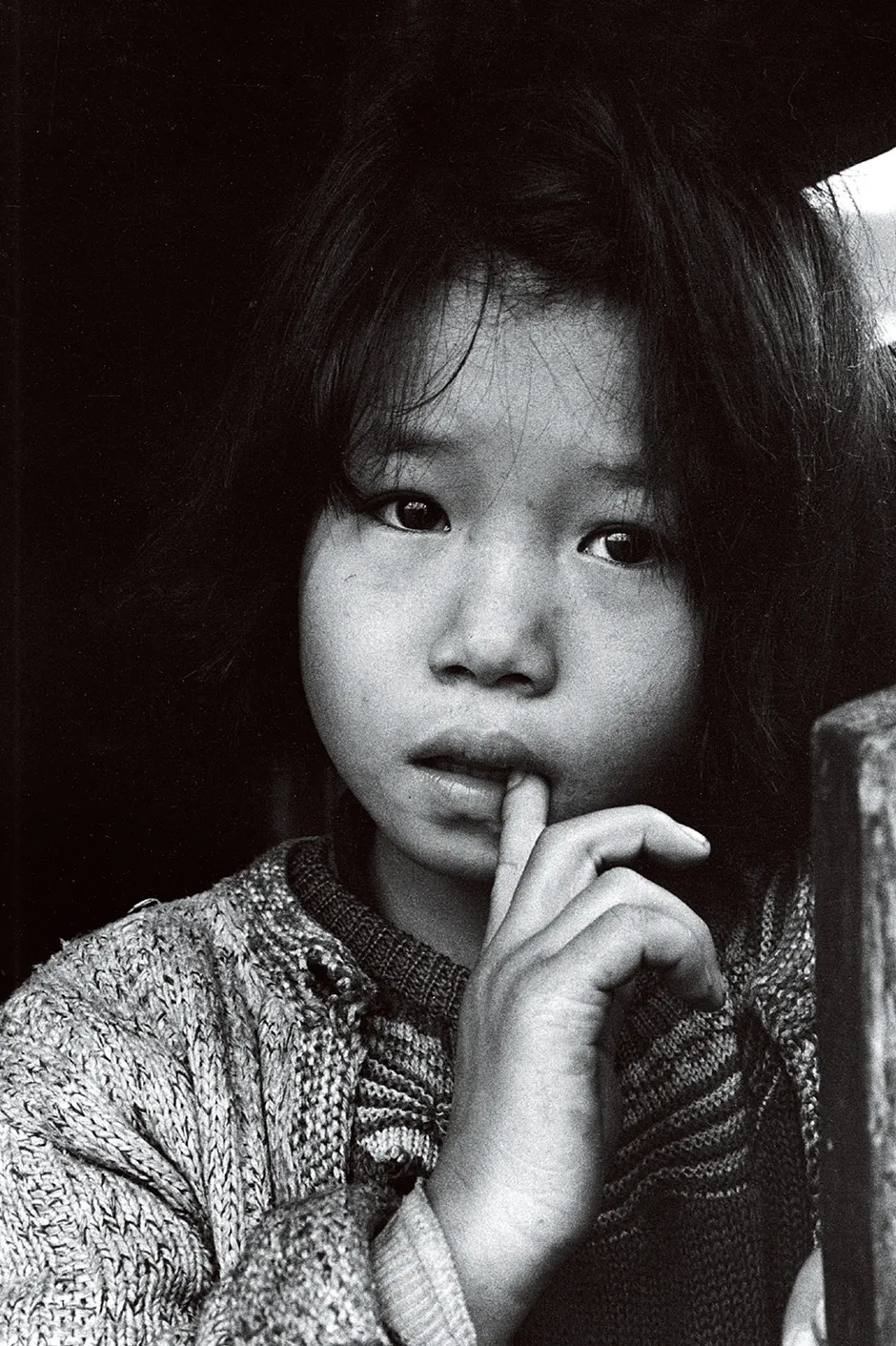

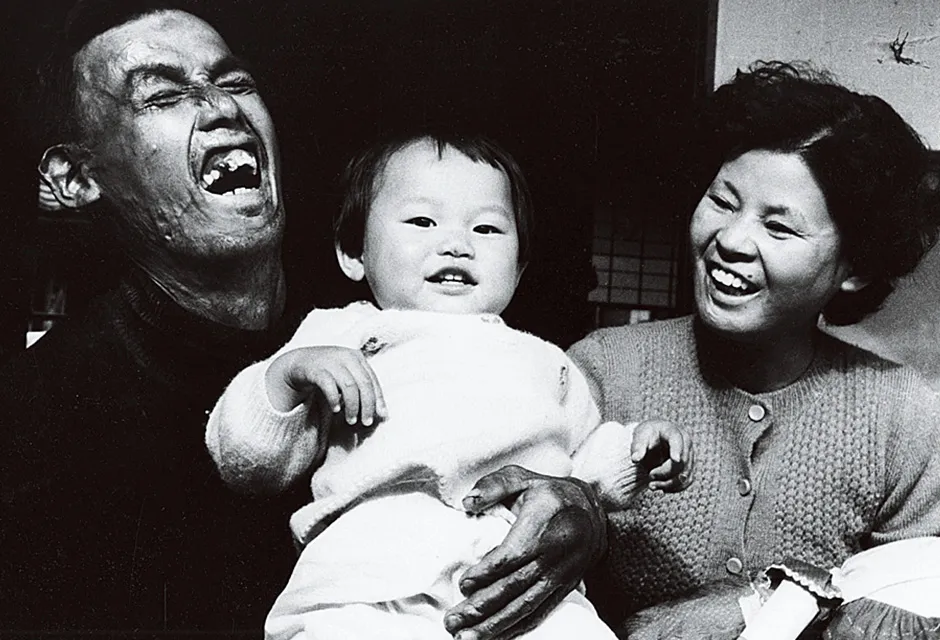

Domon also focused his lens on the harsh realities of postwar Japan, including the homeless, shoeshine boys, and wounded soldiers on the streets, refusing to avert his gaze. He brought to the world of Japanese photography a realism-based approach that faced reality head-on, aiming to inspire social change.

His approach emphasized a direct connection between camera and subject that was uncompromisingly authentic. Capturing the unvarnished truths of what he saw, Domon distilled the collective sorrow, joy, and anger of his era into singular images. His realism resonated powerfully with amateur photographers, though Domon himself sometimes struggled to find his own thematic direction.

He eventually found his way to Hiroshima, documenting the lives of the atomic bomb survivors 12 years after the war. His photography had a profound impact on the public as people got to see stark images of ordinary people who continued to suffer.

Despite a later battle with illness, Domon continued to photograph from a wheelchair until he fell into a coma from which he never recovered, living 11 more years, surely sustained by a fierce will to document life in photographs, his biographer believed.

Ken Domon viewed photography not as a mere pastime but as an art form. Driven to make photography socially and culturally meaningful, Domon’s intense gaze lives on in his photographs, carrying his legacy forward to this day.

Japan’s First Museum Dedicated to Photography, Inspired by a Love of Domon’s Artistry

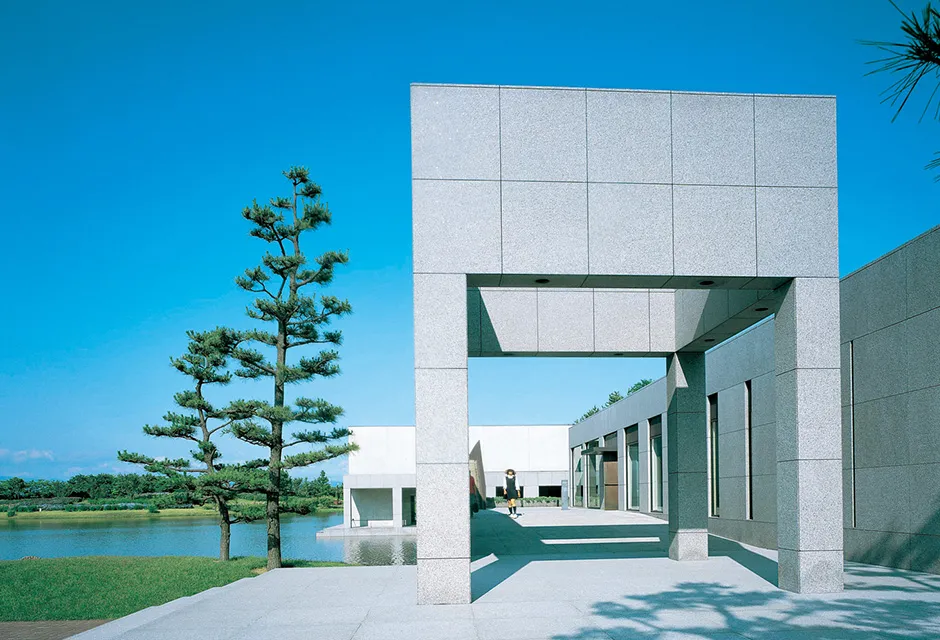

The Ken Domon Museum of Photography stands on the banks of the Mogami River, in Sakata City’s Iimoriyama Park.

The idea to build the museum emerged in 1974, when Domon expressed his wish to donate all his works to Sakata City. As Japan’s first museum dedicated to photography, the project faced numerous challenges, complicated by a devastating fire in 1976. A site was finally selected two years later, along with a plan to turn the site into a cultural park centered around the museum, but fundraising had stalled.

In 1979, as Domon fell gravely ill, and realizing there was no time to spare, Sakata City decided to proceed using its own funds. To cover the shortfall, they issued a nationwide call for donations.

In 1981, the Ken Domon Museum of Photography Support Committee was established to spearhead a large-scale fundraising campaign, led by Saburo Sato, former director of the Homma Museum of Art, and joined by political and business leaders from the city and prefecture. Museum staff member Kayoko Otake recounts, “The outpouring of support was a testament to the respect everyone had for Domon. There was a strong drive to complete the museum while he was still alive to preserve Domon’s works and legacy for future generations.”

The building was designed by Yoshio Taniguchi, the son of Domon’s close friend Yoshiro Taniguchi. Both were renowned architects of their time. Yoshio visited Sakata many times to inspect the site and design the museum’s architecture to blend well with the natural surroundings. He reviewed all of Domon’s works, familiarizing himself with Domon’s artistry and personality, and engaged with Domon’s artistic circle before designing the interior of the museum.

Esteemed artists Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988), Yusaku Kamekura (1915–1997), and Hiroshi Teshigahara (1927–2001) contributed artwork to the museum in homage to their late friend.

With the museum designed by one of Japan’s leading architects, enlisting the help of a famous sculptor, graphic designer, and flower arrangement artist, the museum opened in October 1983.

With snow-capped Mt. Chokai in the background, you head toward the museum and are greeted by a nameplate designed by Yusaku Kamekura upon opening the massive front door. Once inside, a corridor with dimmed lighting to foster contemplation leads you to an exhibition room with Domon’s photographs. Down the next corridor, you come to a window where you can reflect on a courtyard sculpture by world-renowned sculptor Isamu Noguchi named “Domon-san.” Then, rest briefly in the Domon Ken Memorial Room, with its lake view through picture windows.

In the last exhibition room, you can see a garden through the tall, narrow windows designed by flower artist Hiroshi Teshigahara, yet another facet of Domon’s world.

Ken Domon passed away in 1990, without ever seeing the completed museum. Yet his legacy lives on, immortalized within these walls, perpetually capturing the essence of the Japanese spirit for generations to come.