Special Feature

A Visit to the Homma Museum of Art

The Homma Museum of Art is a pioneer among regional art museums, occupying an important place in the hearts of Shonai region residents. The property had its beginnings in the latter part of the Edo Period (1603–1868), when Homma Kodo (1757–1826), fourth head of the family, erected a villa called Seienkaku and created the adjacent Kakubuen garden. Opened to the region’s residents in 1947, it was Japan’s first privately-owned museum and began forging a new history.

The Homma family opened the museum with the public-spirited mission of boosting the public’s confidence in the postwar period by exposing them to Japan’s traditional culture. Since then, the museum has played an important role in fusing culture, nature, and art.

An Expression of Japanese Beauty and Regional Pride

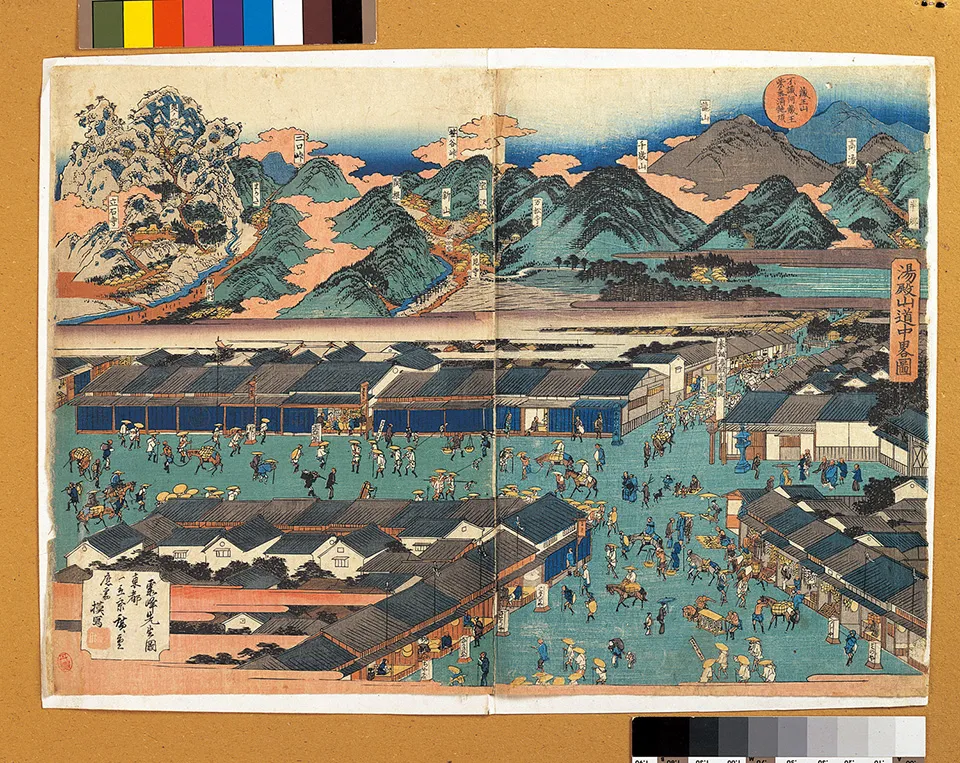

Public spiritedness toward the Dewa Shonai region has long been a tradition in the Homma family of Sakata. Kodo, the fourth head of the family, was an astute merchant who founded many local businesses.

He traded with Ezo (present-day Hokkaido), established himself as a wholesale merchant, participated in trading at Sakata Port, and branched out into constructing his own vessels so as to conduct domestic maritime trade.

He accomplished all of this, while safeguarding the family’s wealth and status. The family’s motto of working hand in hand with the community, espoused since the days of the first head of the family, has been followed over the succeeding generations and contributed to Sakata’s development, as was explained by late family head Makiko Homma.

For example, Kodo provided alternate employment in winter for men who unloaded and transported goods from the port at other times of the year. He built the Seienkaku villa and the Kakubuen garden, which were completed in 1813.

After Seienkaku villa was built, it served as a rest stop for the Sakai clan, lords of the Shonai domain, when they came to inspect their lands. After 1868, when the feudal system was abolished, the villa was used for hosting important guests and high government officials. But the country was ravaged during the course of World War II, and the lives of many people were left in jeopardy following Japan’s defeat. The Homma family’s prosperity was also affected, but even so, the family decided to use its wealth for the community and opened the villa and garden as an art museum.

Buoyed by the region’s expectations, Seienkaku and Kakubuen opened as the Homma Museum of Art in May 1947, to help raise people’s spirits amid postwar devastation and contribute to the advancement of art and culture. As the country’s first postwar private museum, the Homma family’s villa, garden, and art treasures were opened to the public, giving the community renewed hope amid the ruined city.

The museum established a foundation in 1965, to which the Homma family donated its artworks to create a collection of ancient to contemporary art.

Kakubuen Garden, a Tranquil Retreat

In January 2012, Kakubuen, and its view of Seienkaku, were designated a National Garden of Scenic Beauty under the name Hommashi Bettei Teien (Homma Residence Garden).

The garden, designed for strolling around a pond stretching north to south, with Mt. Chokai in the distance, is renowned for the fine quality of the landscaping techniques that go into producing its exquisite vistas. The garden’s tranquil atmosphere and verdant nature let visitors forget that they are in the middle of an urban area.

According to Tatsuharu Abe, who has been photographing the garden for 40 years, “It’s possible to hear great spotted woodpeckers calling from the pines at Seienkaku, encounter kingfishers outside the Ikenohata lounge, and enjoy the fragrant scent of holly near the pergolas where visitors can pause for a rest.”

Abe also notes, “The garden’s scenery changes over the seasons but the plantings appear different depending on the hour of the day as well. Sunlight slanting through the trees and breezes also change day by day, bringing continual surprises when taking photographs.”

Over its long history, the beauty of Kakubuen’s greenery has only deepened as the years go by. The garden’s richness and depth can be experienced even more fully if visitors close their eyes and keep their ears open.

The Eternal Beauty of Japanese Culture

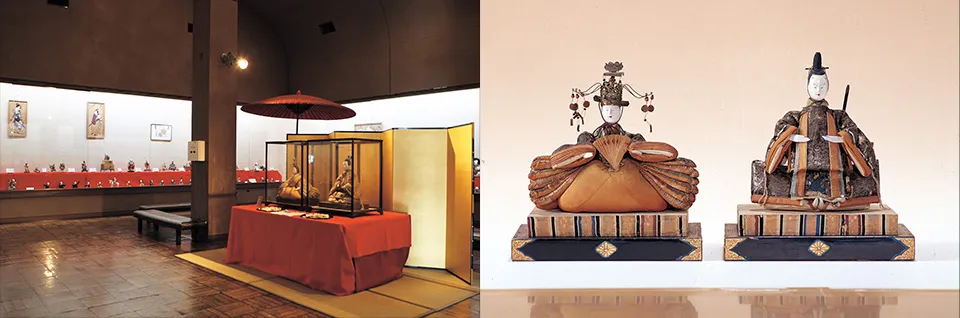

The Homma Museum of Art’s collection encompasses some 2,700 objects. Museum director Akio Tanaka says, “The museum has been open for 66 years, and our collection includes some works that were donated in connection with exhibitions or that we purchased. But most of the important cultural properties and other exhibits in the museum were donated by the Homma family, and they form the heart of our collection.”

The most representative of those are gifts the Homma family received from the Sakai clan or the Uesugi clan, prominent daimyo feudal lords. Many have been designated by the national or prefectural government as cultural properties and trace the history of interactions between daimyo clans and the Homma family.

They include numerous old documents and books, haiku collections, and tea ceremony implements. Symbolic of the Homma family, they are put to use for scholarly and public welfare purposes and laying the groundwork for local haiku poetry and tea ceremony in Sakata.

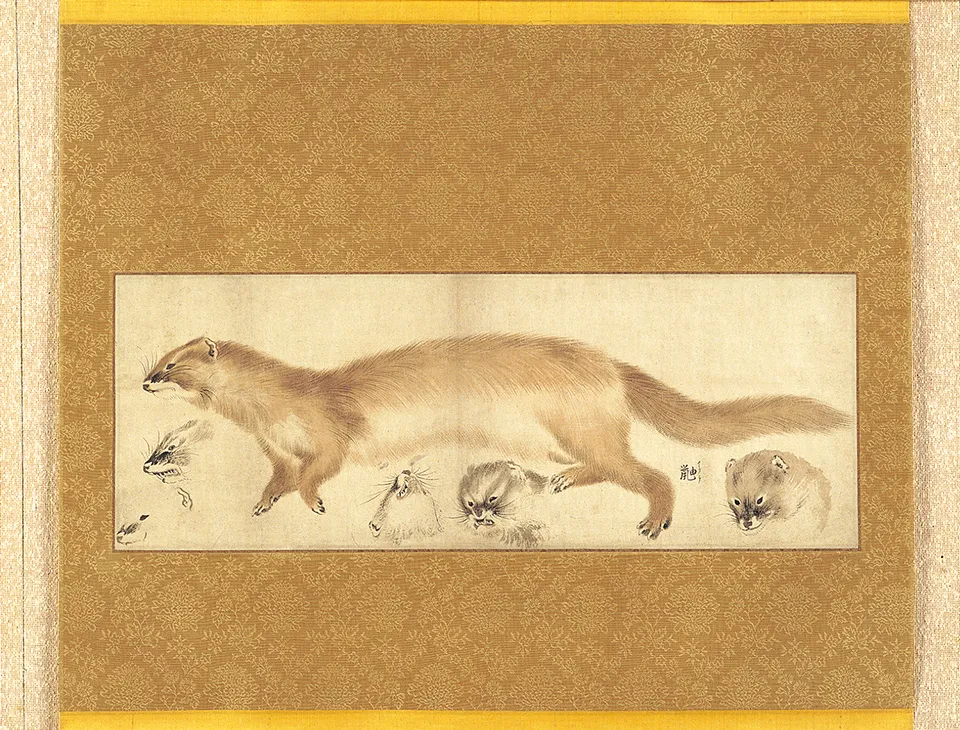

“The Homma family’s heyday was during the Edo Period, so they also collected numerous pictures from that era. Successive museum directors have worked hard since the museum’s opening to expand the Edo Period collection of pictures accumulated at the time Seienkaku was built,” adds Tanaka.

The museum’s collection of antique art grew with each successive period.

Tanaka describes the pleasure that coming into contact with such prized objects brings: “Some of the older items in the collection date from 1,300 years ago, and even most of the newer ones are at least 100 years old. These objects stimulate the imagination when we gaze at them. For example, a tea bowl might have been handled by the greatest tea ceremony practitioner, Sen-no-Rikyu himself. Or, what did someone from long ago feel when they looked at a particular picture? I hope that visitors will take the time to commune with these objects, that transcend the boundaries of time.”

Early Modern and Contemporary Art Works

The museum has devoted much effort to collecting artworks and holding special exhibitions. In the past, the museum hosted frequent exhibitions of works of national treasure caliber or of famous artists active in the major cities.

“We were able to do so because at the time, there were fewer museums in the country, and the Homma family name was itself a big draw for the museum. The first two directors, Junji Homma (1904–1991) and Yusuke Homma (1907–1983), were the driving force behind those exhibitions. They planned extensive special exhibitions, expanded the collection, and worked to build a fine nationwide reputation for the museum.”

Many artists donated works, or the museum purchased some from them each time, when later special exhibitions were held, contributing to a growing store of works held by the museum.

Today, special exhibitions are organized by curators Seiji Abe and Takashi Sudo. These two young men have brought innovative ideas to the museum’s displays, experimenting with different ways of presenting the museum’s collections of art old and new to visitors in illuminating and instructive ways.

Set in timeless surroundings and offering exhibits that provide a window to the past alongside contemporary pieces that open the door of inspiration, the Homma Museum of Art is a place that connects all who visit it with the beauty and history of both Shonai and Japan as a whole.