Special Feature

150 Years’ History of The Matsugaoka Reclamation Site

“With moral virtue as its guiding principle, the Matsugaoka Reclamation Site shall create industry to contribute to the nation and serve as a model for our society.” (From the General Principles of the Matsugaoka Reclamation Site, adopted in 1926)

The silk textile industry, which began with the Matsugaoka reclamation project, helped modernize the Shonai region. The samurai who cleared the land, supported by encouragement from Saigo Takamori (1828–1877), an influential Meiji era figure, overcame the many difficulties the project faced. Their strong resolve lives on in the people of Shonai today. Here is the story of the silk weaving industry in Shonai, from its birth to its flourishing.

The Beginnings of the Matsugaoka Reclamation Site

In the civil war with the new Meiji government forces in the late 1860s, the former Shonai domain’s forces were defeated. In August 1872, the 3,000 former samurai of the domain put down their swords and took up hoes, trudging nearly eight kilometers from Tsurugaoka Castle toward the virgin forest of Mt. Ushiroda in the foothills of Mt. Gassan in what is today Matsugaoka. They began clearing the land, felling huge trees and prying their roots out of the ground, cutting down vegetation and performing other physically demanding tasks day in day out, in all kinds of weather.

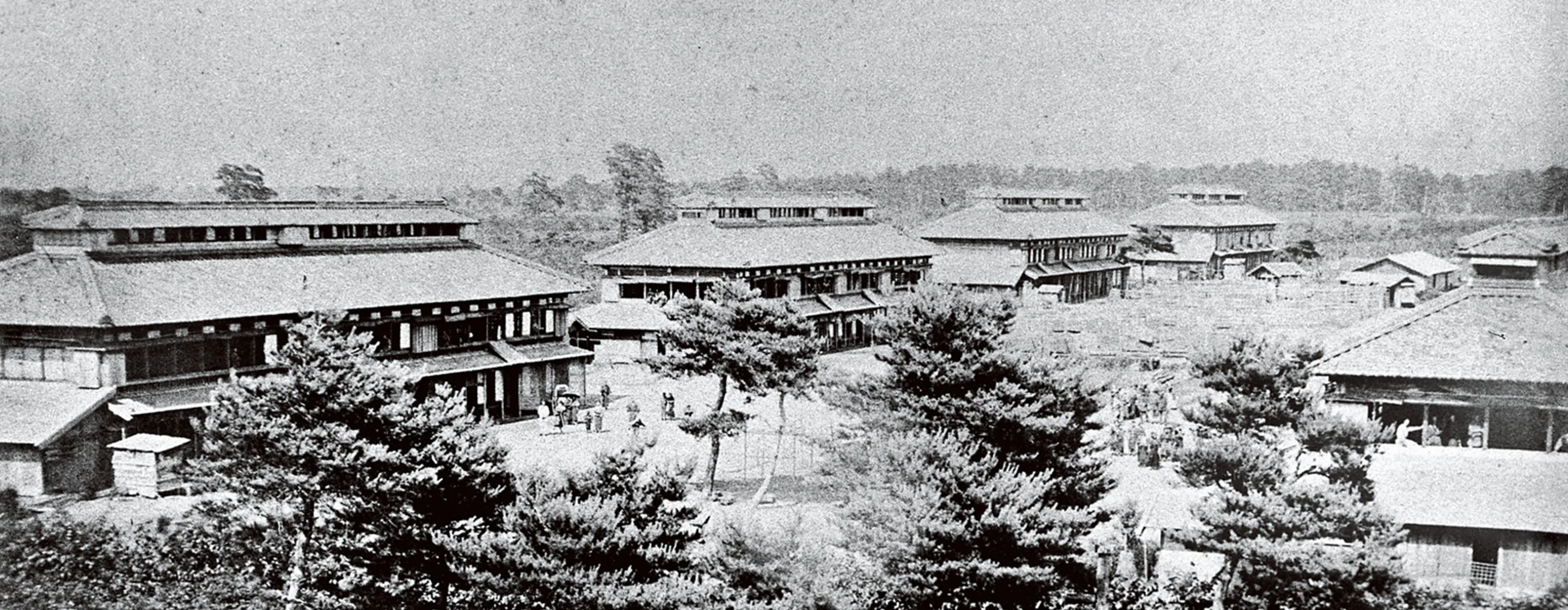

Two years later, the former samurai had cleared around 311 hectares of land. They began growing mulberry in 1873 and the following year traveled to what is present day Isesaki City, Gunma Prefecture, the leading center for sericulture at the time, to learn about silkworm raising. Returning to Matsugaoka, they began building and completed the Matsugaoka Silkworm Breeding Center, where they raised silkworms, prepared egg-laying cards for the silk moths to lay their eggs onto, and began silk reeling operations.

By 1877, a silkworm rearing house had been erected, and land which had been forest just five years earlier was now covered in mulberry fields and boasted the largest silkworm breeding facilities in the country. At the time, raw silk was an important export commodity, and Matsugaoka became a silk producer, helping Japan prosper. The people plunged wholeheartedly into their work, determined to create a more positive image of the former Shonai domain, which had acquired a negative reputation because it had fought against the new government.

They walked to the site from Tsurugaoka’s castle town every day, felling trees that came crashing down with a thundering sound making for a scene comparable to that of a battlefield.

In 1876, inhabitants of the Shonai region rebelled in efforts to demand the return of overpaid taxes, as a result of which subsidies from the local government for the Matsugaoka reclamation project were cut off. In 1878, a ruling on that rebellion was handed down requiring that Matsugaoka return three years’ worth of subsidies to the local authorities, which put the site into a precarious financial position.

With money scarce, Matsugaoka closed down some of its silkworm rearing rooms, sold its mulberry bushes and reduced the scale of operations. It successfully overcame its difficulties and gradually revived the business, thanks to the passion of its founders for sericulture and strong demand for silkworm-egg cards.

Sericulture became established throughout the Shonai region, and the Matsuoka Silk Mill opened in Tsuruoka in 1887. Following this, several large silk weaving sheds were built, a school was opened to train craftsmen in the trade, and ironworks were set up to produce looms, establishing an industry cluster in the region.

This is how Tsuruoka became one of the country’s major silk producers and embarked on the road to modernization.

The Path of Matsugaoka’s Silk Textile Industry Expands to Tsuruoka

With the start of sericulture at Matsugaoka, silk thread was produced and woven, related industries clustered on the site, and Tsuruoka grew into one of Japan’s major silk producers. At one time, close to 60 percent of the working population of Tsuruoka was employed in the silk weaving industry.

Between the 1870s and the 1920s, Japan became a major silk thread producer, producing everything from silk thread to silk textiles and silkworm-egg cards, and sericulture became an important export industry.

The Matsuoka Silk Mill, which began operating in Tsuruoka in 1887, adopted improved techniques after learning about the latest silk reeling technology from the Tomioka Silk Mill, now a World Heritage site in Gunma Prefecture. Working with the Matsuoka Silkworm Card Company, the Shonai Sericultural School and others, the mill improved its raw cocoons, producing Matsuokahime and other silkworm strains.

In 1895, the mill developed “habutae” glossy silk cloth for export, for use in Western-style clothing, and in 1898, local resident Toichi Saito invented a power loom. He later obtained a patent for his machine, and this new weaving technology quickly spread throughout the country.

Tsuruoka also later began producing satin weave, a type of satin textile popular abroad. Ironworks for making power looms sprang up in Tsuruoka and the Dyeing and Weaving School was opened to provide vocational education. The silk textile industry thus had a broad impact on the region.

In 1913, an additional facility of the Matsuoka Silk Mill was set up in what is today the Matsuyama district of Sakata, and operations were eventually consolidated at that site in 1937.

Around that time, semi-synthetic fiber rayon had been developed abroad, and a global recession had begun. World War II also meant the end of many businesses in Japan.

Chikara Seino, president of Matsuoka Co., Ltd., explains that “After the war, several businesses got together to form the Tsuruoka Fabric Industry Cooperative, but competition from China made things very difficult.”

Using technology developed in the silk industry, the Matsuoka Company branched out into manufacturing aircraft parts while continuing to produce silk textiles.

“Since the days when Matsugaoka was reclaimed from the wilderness, we’ve been in a continual process of letting go of the old and adopting the new. While our business has changed, the silk industry has continued to be supported because it’s a cultural and historical asset of the region.”

Looking to the Future of Matsugaoka with Silk and Wine

Tangible and intangible assets of Matsugaoka responsible for the development of the silk textile industry in Shonai have been passed down to the descendants of the pioneering samurai. In recognition of its historical and cultural legacy, the area was recognized in 2017 as a cultural property and national heritage of Japan as “Samurai Silk–Witness to the modernization of Japan in Tsuruoka.”

Upon receiving this designation, Tsuruoka formed the Tsuruoka Samurai Silk Preservation Society Office and launched the Matsugaoka Craft Park project.

Project member Kyosuke Yamato, CEO of Tsuruoka Silk Co., Ltd., explains that the park was intended to bring creators together. It includes a display area describing the history of the silk textile industry, its present and its future, and setups offering hands-on experience in silk reeling and dyeing to expose visitors to silk in all its aspects.

An on-site shop, Kibiso, plans to sell silk fabric, which is a biodegradable and sustainable material, in the future. Cross-industry and industry, academic and government collaboration will create new businesses as Matsugaoka moves toward the future.

In advance of the project, a winery called Pino Collina opened in Matsugaoka in 2020. The winery’s president, Tsuyoshi Hayasaka, relates that the area’s scenery inspired him to start this new business.

“The vineyards of the World Heritage Site of Langhe, Italy, with the Alps in the distance, reminded me of the landscape of Matsugaoka and Mt. Gassan. I felt a desire to preserve Matsugaoka, where the pioneering spirit lives on, for the future.”

Happy with Hayasaka’s vision, local landowners leased him their fields, and he acquired and began planting vine saplings.

“Matsugaoka is unique, and just like the story of its origin, the wines produced here are like no others; to me, wine-making is a kind of art. I want to create a local wine culture here, and contribute to the community with an eye on the future.”

From mulberry bushes to vines: a new chapter in the story of Matsugaoka reclamation begins.