Special Feature

Dewa Shonai and Japanese Sword Culture

The sword has long been a symbol of both authority and spirituality in Japan. It also is a weapon that has shaped the course of history through mortal combat. When steel is tempered, sharpened, and made strong, it develops a sense of beauty that can be both serene and frightening. Such craftsmanship can only be a reflection of pure Japanese pride.

Preserving Sword Culture

Japanese swords are a testament to the lifestyles of its ancestors. While an increasing number of young people are pursuing their interest in Japanese swords today, the fate of Japanese swords was not always so secure. In fact, it was two men from Shonai who managed to come to their rescue.

What we know today as a Japanese sword was originally developed at the end of the Heian Period, around the 11th century, when Japanese swordsmiths began adding curvature to the straight swords that had been brought over from mainland China. It was a meticulous process of heating and tempering the steel numerous times, and wrapping the softer iron core, or Shingane, with a harder outer skin, called the Kawagane. These swords were not only weapons; they were also greatly revered as status symbols. A sword was a warrior’s spirit, a gift to be bestowed upon others, a prized work of art, or even a ceremonial item. In one such ceremony, the Sokui-no-Rei (Ceremony of the Accession to the Throne) the Emperor of Japan inherits Three Sacred Treasures: the sacred mirror, the sacred jewel, and of course, the sacred sword. Continuing this legacy, Emperor Naruhito formally received these three treasures on October 22, 2019.

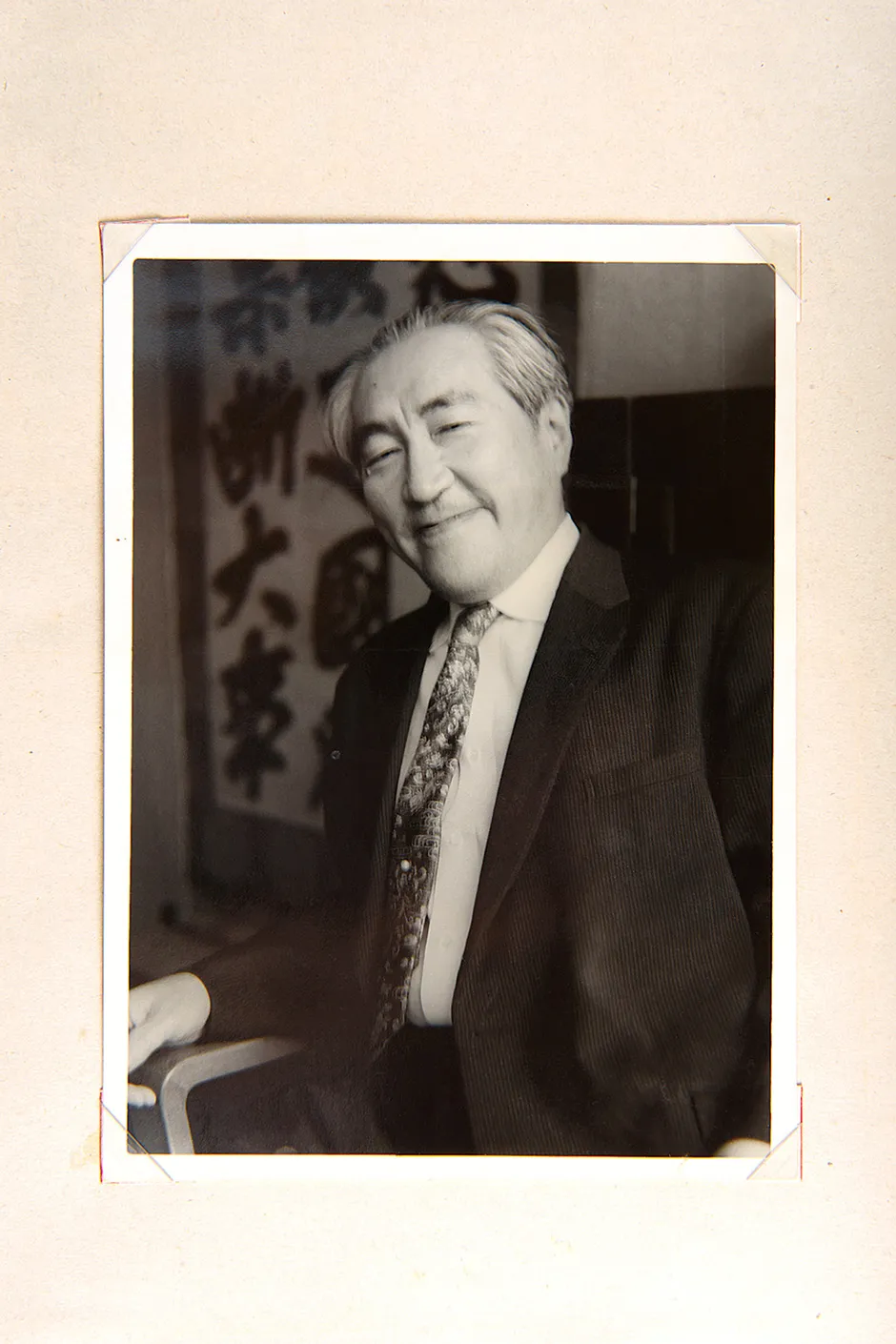

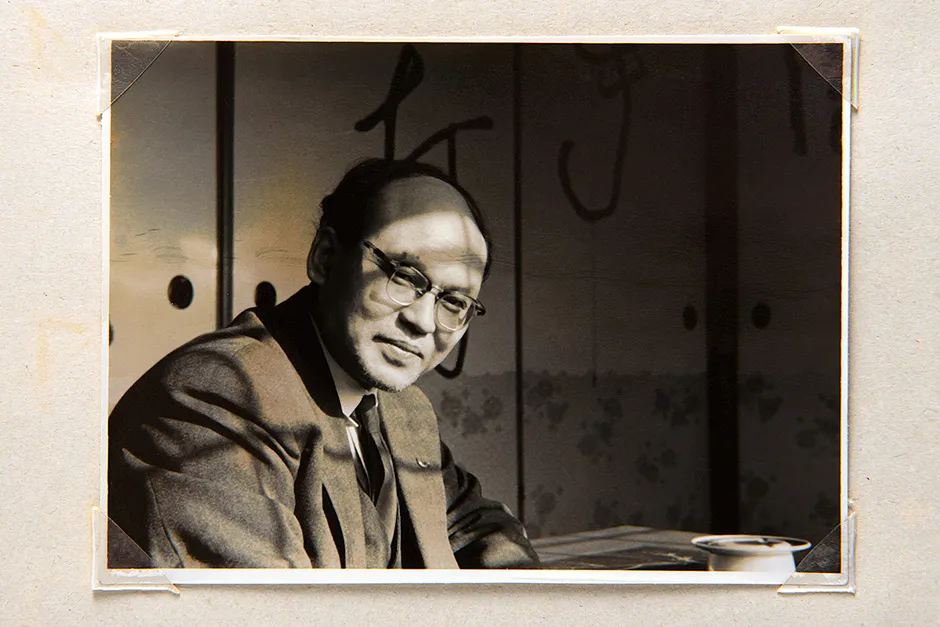

However, following Japan’s defeat in World War II, the Occupation Force of the Allied Powers issued a command that all swords throughout the nation be forfeit. In response, two men stood up to oppose this order: Kunzan (Junji) Homma (1904–1991) and Kanzan (Kan’ichi) Sato (1907–1978).

Kunzan Homma was born in Sakata City to a paternal line of sword enthusiasts, and grew up with no less than 2,000 swords in his childhood home. His cousin, Kanzan Sato, born in Tsuruoka City, also received tutelage under his uncle, a Chinese poet and fellow sword enthusiast by the name of Chiku Tsuchiya (1887–1958). Together, Kunzan and Kanzan became two of Japan’s leading sword researchers.

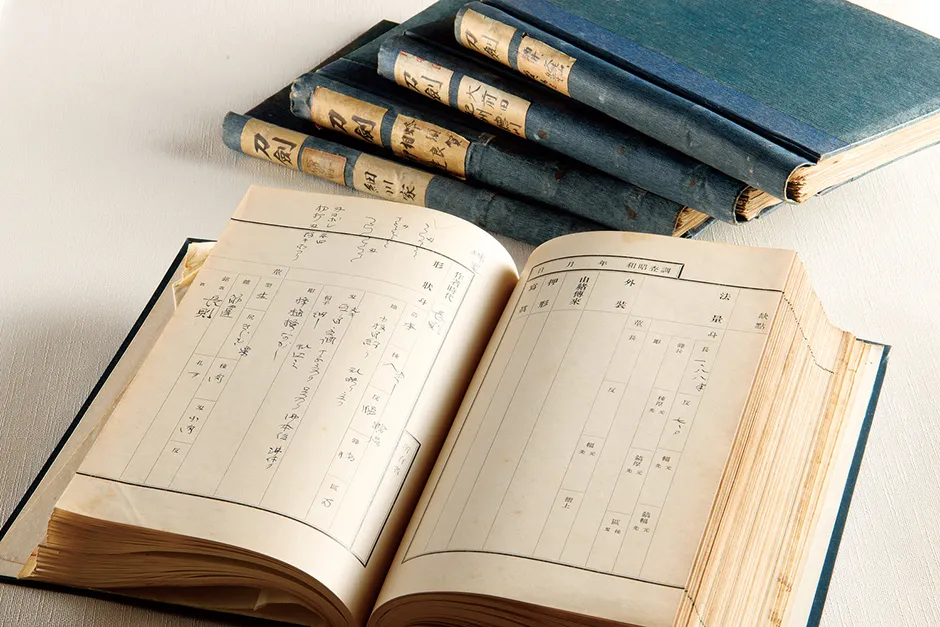

Kunzan was already known for his work in ancient swords (Koto) in Tokyo when the order to forfeit all Japanese swords was issued. Setting to work immediately, Kunzan and Kanzan called upon Japan’s sword enthusiasts, petitioned the occupying forces, and overturned the order. Then in 1948, under the advice of Colonel C. V. Cadwell, he and his colleagues around the country founded the Nihon Bijutsu Token Hozon Kyokai (NBTHK) to ensure the preservation and continuation of Japanese sword culture. It cannot be overstated just how much Kunzan and Kanzan contributed to the preservation and promotion of Japanese sword culture over the years.

The NBTHK was founded and initially chaired by art collector Moritatsu Hosokawa (1883–1970), with Kunzan and Kanzan assuming the roles of executive director, but Kunzan would soon go on to become the second chair of the foundation. Now, to carry forward the present and enduring Japanese sword culture, Tadahisa Sakai, former director of the Chido Museum and 18th head of the Sakai clan, former feudal lords of the Shonai domain, sits as the NBTHK’s 10th chair.

The Great Swords of Dewa Shonai

The Chido Museum is located on the site of the former Sakai clan estate, in what used to be the third bailey of Tsurugaoka Castle, and is home to two long swords (Tachi) that have been declared National Treasures. Sakai was kind enough to explain the historical significance and distinctive aspects of these two swords.

“The long sword inscribed ‘Sanemitsu’ was gifted to the Sakai family at the most opportune time by Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582), a great daimyo of the warring states period (1467–1615). If Nobunaga had waited just three months longer, he would have died in the coup of the Honnoji Incident (1582), and we would not have the sword here with us today.

I think that’s a neat little bit of historical trivia.” The long sword inscribed “Sanemitsu” dates back to 1185–1333, and was designated a National Treasure in 1953.

Its creator, Sanemitsu, was a disciple under the famous Osafune Nagamitsu, the founder of the Osafune School of Bizen Province (present-day Okayama Prefecture). It has a noticeably wide blade, and it exudes an aura of magnificence and grandeur. It was originally gifted to Sakai Tadatsugu (1527–1596), head of the first generation of the Sakai family. The year was 1582, and Nobunaga had just defeated feudal lord Takeda Shingen (1521–1573). On his return home, he stopped by Yoshida Castle in Hamamatsu and bestowed the sword upon Tadatsugu as a token of appreciation for his hospitality. The sword mounting that was presented alongside the sword is also designated as National Treasure.

Two years later, Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), the shogun at the time, presented Tadatsugu with the long sword inscribed “made by Nobufusa” in recognition of his exceptional performance in the Battle of Komaki and Nagakute (1584). This sword was created by a Ko-Bizen School swordsmith around 1086–1185. It is slender, with a high curvature at the waist, which adds a touch of elegance to the design. It was designated, along with its sword mountings, as a National Treasure in 1952. The two swords have remained prized family heirlooms of the Sakai family for more than four centuries.

“Swords were meant to be passed on to others, so they don’t often stay in one place for very long over the course of their long lives. And yet here we have two swords that one family was particularly loath to part with, and so they have remained within the one family for generations. It’s possible they were used as spiritual devices to safeguard the household.”

These are not the only swords that have been continuously passed down within the Sakai family. The “Shinano Toshiro,” a “Tanto” dagger crafted by one of the Three Great Smiths of Japan, Awataguchi Yoshimitsu, is also a part of the museum’s collection. Not only is this particular dagger immensely popular with younger generations, Sakai believes it is one of Yoshimitsu’s “best daggers of all time.”

The Work of a Swordsmith

A sword is born by the expertise of many experienced hands. Among the many sword-related professions are the togishi, who polishes the blade; the sayashi, who creates the wooden sheath; the tsukamakishi, who wraps the hilt; and the metalworker, who shapes and engraves the embellishments that can be found on the sword; but the artisan who works closest with the blade is called the swordsmith. Tsunehira Kanbayashi is one such swordsmith, and he is the only swordsmith in Yamagata Prefecture to keep this tradition alive. Born in Tsuruoka City, he now owns and operates his own smithy in Yamagata City, and he is heavily involved in Japan’s sword-smithing community.

“I remember there used to be a knife store in Tsuruoka that would display swords for the New Year. I was fascinated by their unusual beauty, and I remember being unable to take my eyes off them.” Kanbayashi had always enjoyed crafting things from an early age, but it wasn’t until middle school that he learned of sword-smithing as an occupation, when he heard in the news that swordsmith Yukihira Miyairi (1913–1977), whom he would eventually apprentice under, had been designated as a Living National Treasure in 1963. “When I got to high school, I’d often go to see the famous swords on display at the Chido Museum. I think it was those great swords that really pushed me onto my future career path.”

Kanbayashi became an apprentice under Miyairi in 1967. He was only ever given menial chores to complete for the first five years due to the sheer number of other hopeful apprentices, but as he worked his way up to working alongside his mentor, Kanbayashi gradually rose through the ranks to become one of Miyairi’s top apprentices. Within ten years, he had gone solo.

“Swords are weapons, this is true, but it’s their beauty that really captivates me. I really do believe that out of all ironmongery only Japanese swords bring out the beauty to be found in steel.” There are Japanese swords, and then there are the “great” Japanese swords; those that are “inexplicably pleasing to the eye, with no room for discomfort.”

“What I particularly love are ancient ‘Koto’ swords. Think of the mountains: you’ve got the ridges that stand out, and then you’ve got the dense woodlands spread beneath. You know the clouds that gather in that sort of location? I think the swordsmiths of old sought to reflect these sorts of natural phenomena in the temper patterns of their blades. You need that sort of idealized image in your head in order to bring out the true beauty of the sword. The greatest ancient “Koto” swords are a reflection of the great scenic wonders of Japan, which makes them pleasing to the eye. Those are the types of swords I want to make.”

Swords may have been initially designed as tools of war, but it is through the art of skilled forging and polishing that they are truly brought to life. In this sense, it could be said that a sword is imbued with the spirit of those who have dedicated their lives in the purest pursuit of beauty.